We stopped hosting software

Feb 9, 2026You read it right. That’s the sentiment I keep hearing from companies around me - and especially from recent firsthand experience. Every time my team considers adding a database or a message queue, we ask ourselves: would it be better to manage a host at all?

Our web application uses Redis as an authentication session store. It has always been a low-load, low-memory service. When we migrated to Kubernetes in late 2024, we moved from a self-hosted, single-pod Redis running in Docker Swarm to Memorystore. Before that, we felt compelled to test even minor Redis releases. It was painful overall on Swarm, and for reasons I no longer fully recall - possibly related to health checks - the instance took around seven minutes to restart. The deploy engineer would visibly tremble every time the application was updated.

With the managed offering, we stopped caring. Minor release? We don’t even notice. Health or cost? We barely think about it. We threw the database credentials into the secret store and effectively forgot the service existed - software as a service in the most literal sense.

Until - fast-forward a year - a developer reached out saying that temporary environments were consuming his queue.

By then, it had been some time since we introduced temporary (preview) environments, allowing the wider team to run quick tests, verify experiments, and fix bugs that would never reach main staging. These environments were designed to reuse parts of the larger staging infrastructure, acting as a Helm overlay for the application itself - new app, old dependencies. The key-value store was one of those shared parts. The result: a “preview” app started running jobs scheduled for actual staging.

By that point, we had already crossed the great Bitnami paywall by stopping to use their Helm charts and adopted Dragonfly as a safe Redis alternative. It felt reassuring: an established product, a Helm chart, a Kubernetes operator, and all the usual tooling. We didn’t use it for the most critical parts of the stack, but it worked well for smaller, less business-critical features. To fix the staging→temporary environment issue, we needed high availability. Dragonfly’s operator supports this nicely, providing a hot-standby replica.

As I read through the documentation, it became clear how simple this had become. It was mostly a matter of specifying a replica count: “one pod” versus “a full hot-standby cluster with pod disruption handling and scaling rules.” Add affinity settings, and you can make it as resilient as you like.

Somewhere along the way, I realized I had forgotten how different running software is today compared to before. Deployment is fast. Reliability is often assumed - subject, of course, to the operator and platform behaving as intended. Metrics are there by default. This is no longer the world of painstaking Ansible playbooks, hand-written configs, and fragile templates.

Or maybe it is - but we’ve finally built platforms reliable and fast enough to make it feel otherwise.

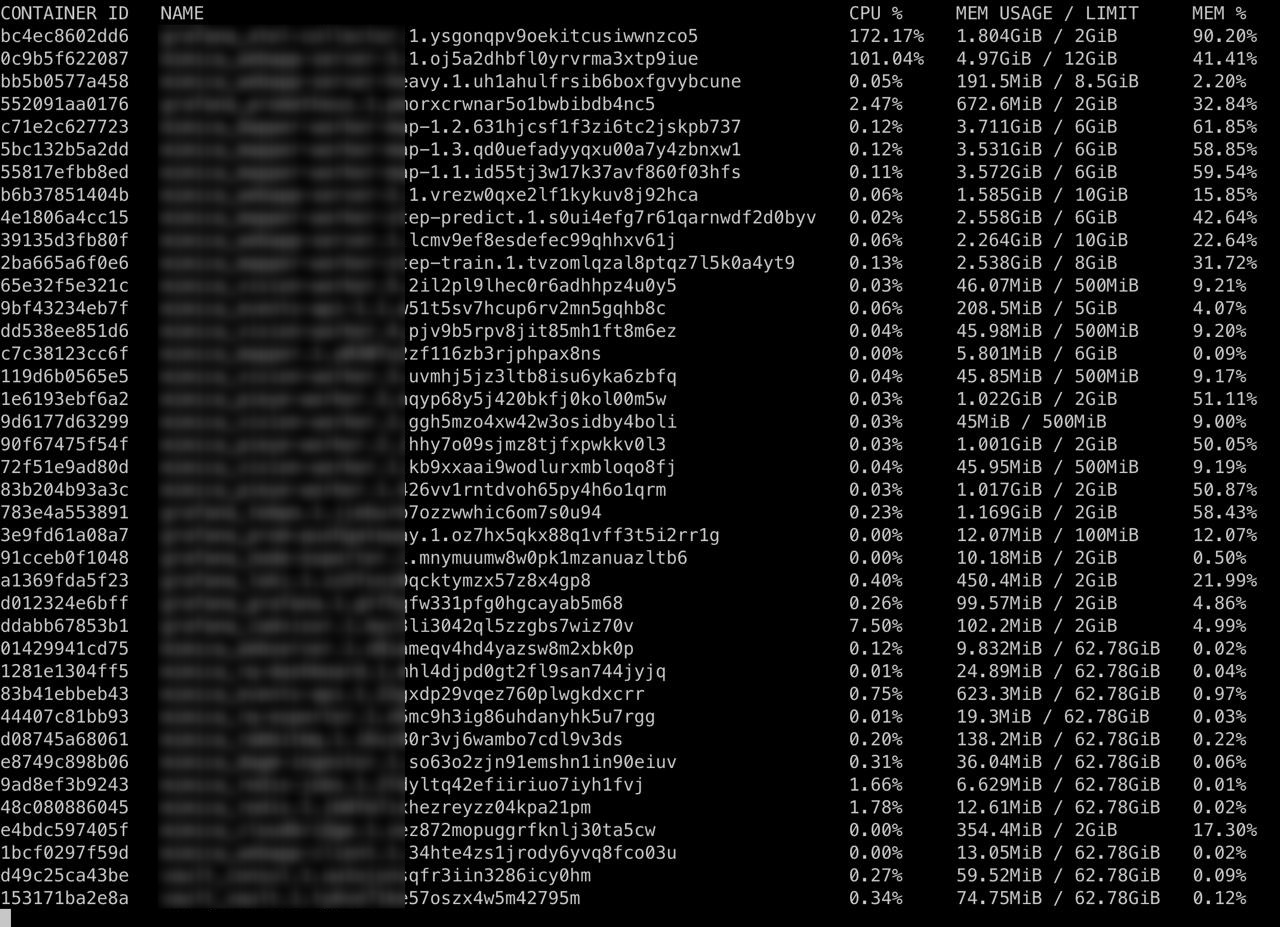

How we used to run docker swarm